‘Police come for us at night’: Belgrade, a crucial but hostile layover city for migrants on the Balkan route

BY| Infomigrants

Serbia’s capital Belgrade serves as a layover for many migrants on the Balkan route. However, the hundreds of Syrian, Afghan or Moroccan migrants passing through every day only have two accommodation options: an overcrowded and remote camp, or the streets and parks of the city.

Achraf takes a pinch of tobacco from the plastic wrapper. Carefully, he spreads it on a thin, translucent sheet of paper, and moistens the edges. The cigarette is rolled then lit, he takes a long puff, which forms a halo of white smoke around him. His gaze lands haphazardly on the horizon. The young man from Casablanca looks exhausted. It has been two years since he fled Morocco, three months since he left Turkey and two days since he arrived in Belgrade. A large hole on each one of his sneakers reveals his black socks.

In the Serbian capital Belgrade, he kills time with three other Moroccan migrants, Mohsen, Osman and Amine, on the concrete stairs of the old main train station which has long been falling into disuse. Once the small group has collected some money, which they say will be “soon”, they plan to take the road to northern Serbia in order to reach countries in Central Europe, from where will go to France or Spain.

The Balkan route, which for many migrants begins in Turkey, has seen an spike this year. According to estimates by the Belgrade-based NGO Klikaktive, almost 90,000 people have entered Serbia since the beginning of 2022, compared to 60,338 for all of 2021, according to combined data from UN refugee agency UNHCR and the Commissariat for Refugees and Migration of the Republic of Serbia (KIRS).

For the migrants who have chosen to cross Serbia rather than Bosnia, another country along the Balkan route, Belgrade is a necessary layover city because of its central location. Taxis or buses coming from the south stop in the capital, while others go north toward the Hungarian and Romanian borders. The layover allows migrants to pause from their journey for a few days and plan the rest of their trip.

‘Slapping, kicking and bludgeoning’

The capital, however, is not a good place to rest. The only reception center in the region, located 30 kilometers away in the city of Obrenovac, is at capacity. On October 13, more than 300 people were camping in front of the center, including 16 unaccompanied minors. Numerous migrants prefer the rare green spaces of Belgrade, like the small park next to the old train station and the bus station.

At dusk, small groups of people settle with their backpacks on the withered grass before spending the night there. No one lies down on the benches which line the small path, some of which are missing wooden pallets. A small newspaper stand at the park’s entrance offers migrants the possibility to recharge their phones for a few Serbian dinars.

To eat and drink, Achraf and his traveling companions rely on locals, who gave them some food yesterday. “The police come for us at night, so we return here. At the station, they leave us alone.” It is impossible for the young Moroccans to find refuge inside the station: The doors of the imposing yellow building, which the municipality wishes to transform into a museum, is kept locked.

Sleeping outside is an additional ordeal for these migrants, who are weakened by the first part of their journey. Before arriving in Belgrade, many became victims of violence on the borders of Europe: between Greece and Turkey, or between Serbia and Bulgaria. “When the police catch people there, they beat them up. A friend of mine was hit so hard on his head, he later went crazy,” says Achraf.

Migrants and NGOs regularly denounce the violent pushbacks at the Bulgarian border with Turkey. Last May, Human Rights Watch reported that “Bulgarian authorities beat, rob, strip and use police dogs to attack Afghans and other asylum seekers and migrants, and then push them back to Turkey without any formal interview or asylum procedure”.

At the end of 2021, the Bulgarian branch of the Helsinki Committee recorded 2,513 pushbacks from Bulgaria, involving almost 45,000 people. Many pushbacks have also occurred further south, on the border between Serbia and North Macedonia, where Serbia built a barbed wire fence in 2020.

According to the latest data published by authorities on the subject, Serbia prevented more than 38,000 crossing attempts at its southern border in the same year. The deportations were “often very violent” and included “slaps, kicks, blows with rubber sticks, insults and threats”, says Nikola Kovačević, a human rights lawyer.

‘People come every day’

In order to find solace in the Serbian capital, migrants stop at the Wash Centre, located five minutes away from the bus station. Opened in 2020 by the Collective Aid association, it allows migrants to take a shower, wash their belongings and drink a cup of tea or coffee. On this cool and sunny October morning, about 15 people have gathered in front of the small building. Seated inside, Karim, a former police officer from Kabul with his hair in disarray, rubs his eyes before picking up a plastic cup of steaming tea.

Today, he came to pick up a few clothes that Collective Aid donates to migrants when the NGO has enough in stock. “I don’t have any money at the moment, so I’m glad they gave me this today,” Karim says, pointing to his gray jogging pants.

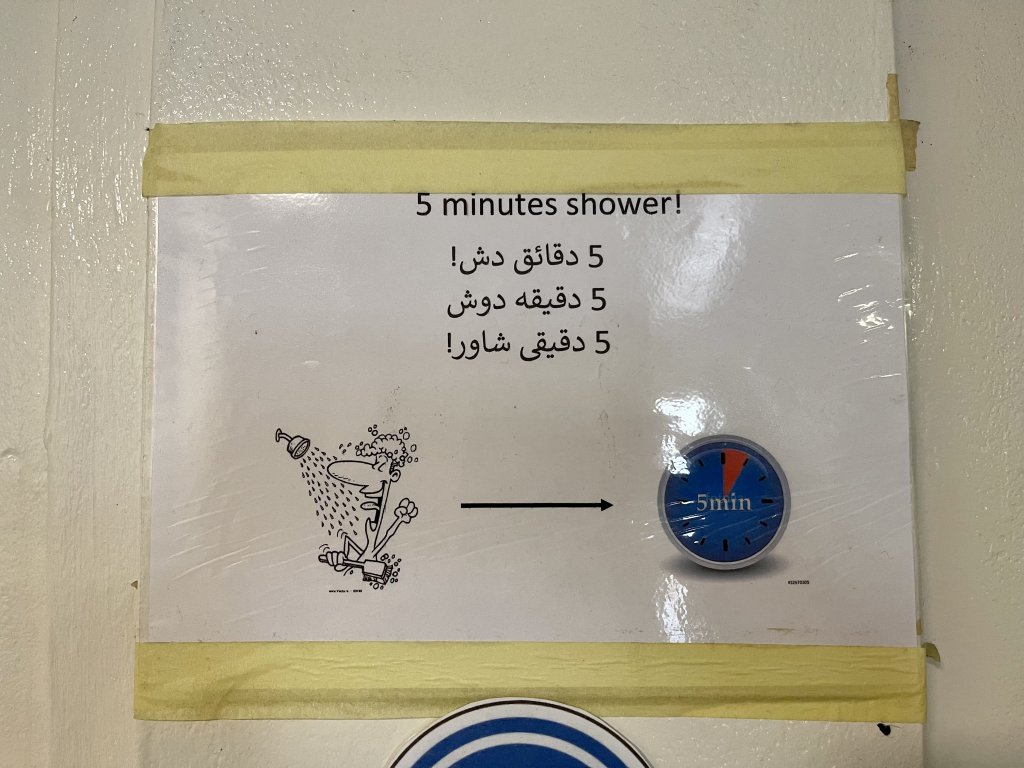

“It’s busy all day here at the moment,” Claudia Lombardo, who runs the Wash Centre with three other volunteers, told InfoMigrants. “Since June, between 70 and 80 people come to take a shower every day, and we run 30 washing cycles.” The center also offers visitors a small place where people can shave and clean themselves. Sanitary products for women are also provided. Moreover, migrants can take a shower every afternoon for an hour.

At a small counter in front of the washing machines, which are stacked on top of one another, a tall young man opens a canvas backpack and pulls out some clothes. Mohamed, 30, has come to Belgrade for the second time in six weeks.

The young Syrian tried to enter Romania from Majdan in the North of Serbia six times. Each time, the Romanian border guards violently pushed him back and stole his savings, he said. “I couldn’t stand the situation there anymore so I came back here to rest a little.” He has been sleeping at the Obrenovac camp the last two nights, where “the mattresses are infested with insects.”

During the day, he comes to the Wash Centre, a place he knows well. “I discovered this place during my first visit to the city. When I arrived here [after leaving Turkey and crossing Greece, Albania and Kosovo], I was exhausted and sick. I wanted to buy medicine but no pharmacy would let me in,” he recalls, as his green eyes are widening.

“I was wandering in the street when I came across the Wash Centre by chance. I found showers there and people I could talk with. It was liberating. They took care of me a little bit.”